The quote (originally in German) belongs to my dear friend Joel Niko.

The process of reworking or giving new meaning to older, respected works is indeed tricky; one has to tread carefully in order to avoid offending the kind of elitists who abide by the 1:1 historical performance practice. Then of course on the other end of the question chain lies the age-old dilemma: Should we just stick to the score, or try to reach what the composers actually have intended? Some pieces are written in such a masterful way that exactly doing whatever’s written there is enough to make it sound beautiful. Make no mistake, this is by no means a defining quality of a “good” composer, but merely a friendly wink to the performers by the composer, who in this case (probably) too is a performer. Absence of such a quality might’ve been completely unrelated to the composers skillset and caused by the limitations of their time. Best example to this would be the notation of syncopated triplets which were written as dotted 8th & 16th at the time simply because of the lack of an another way to notate them.

Here’s the courante from Bach’s 4th French Suite. Intended way is to play the last third of the beat together in both hands, despite the non-triplet notation of the left hand.

Whatever the reason, we certainly don’t have the luxury of always expecting notation to reflect the true intention. Overcompensation is a problem too though. Hungry for a more effective performance, musicians might see a ‘hole’ in their pieces and hastily decide to fill it with concrete. At some point the lowest possible key on Beethoven’s piano used to be an F1 (das ist das große F for fellow german system users) which means todays pianos go more than half an octave lower, opening new possibilities.

Beginning of his Gassenhauer trio. Marked in red are optional keys which didn’t exist in Beethoven’s keyboard. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature!

Limitations are what make excellent compositions.

One could strongly argue that Beethoven’s (or any other composers) approach to a wider keyboard would’ve been much more than merely doubling the bass notes even deeper. The piece is written in a limited way for a limited instrument, but the parity in-between has been carefully crafted, inspected, approved and published “as is” by the person who we call today a genius composer. In this context even slightly changing it would make it wrong to present it as “a piece by Beethoven”. Even if we keep the melodies, harmonies, etc. the fine detail work by the composer would’ve been eroded.

Though there’s a way! “Changing” a piece is not wrong, as long as we specify that it is different, and who made it different. Look at Godowsky’s incredible arrangements of Chopin’s Etudes: Thanks to the 70 years of rapid advancements in piano technic, Godowsky had the ability to transform Chopin’s works in fundamental ways. This historical example of “recontextualisation / complete paraphrasing” was not the first and definitely not the last time of this happening. By prepending the “Chopin/Godowsky” to the title, the listener now knows that the original composition serves the purpose of being the basis to a transformation. This small and hard to notice difference changes the audiences expectations greatly, as the attention is directed from Chopin’s genius to Godowsky’s attempt of transformation. In a small corner of their mind a kind of worthiness test takes place: did Godowsky’s arrangement skills manage to pair Chopin’s composition skills? If you ask me, absolutely.

What would Bach think if he saw his BWV 857 butchered in Zirkonium like this?

Just do it!

This inevitable comparison should never push anyone away from trying! I can’t imagine the music world with the absence of milestone arrangements like Beethoven/Liszt: Symphonies, Mussorgsky/Ravel: Pictures From an Exhibition, Bach/Busoni: (Anything!), and the list goes on… Do you have a crazy idea like they did? Then please sit down and do your best to realize it! I’m doing my part 🙂

I absolutely love sitting and imagining unlikely scenarios of composers meeting the future. What would Chopin’s improvisations sound like after a (healthy) dosage of late Scriabin works? What kind of ideas would Mozart have if he saw Beethoven’s or Chopin’s music? What would Bach have done with a 32-speaker 3D sound tent in his possession? My project today aims to at least shine some light on that third question.

“Bach would’ve mixed in multichannel surround if he could”

This brings us to the excellent quote in the beginning. I know Joel was probably half asleep at 01:23 as he typed these words, but after giving it some serious thought it actually makes more sense than we both thought it did! Bach would’ve definitely composed in fully spatial audio…

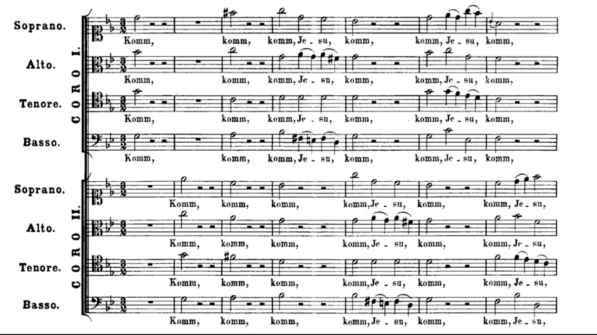

Just look at Bach’s BWV 229 “Komm, Jesu, Komm”. There are two separate choirs on the left and right side. If we check the notes we can easily spot how both choirs sing different parts. They do however merge later in the piece. These are roughly the foundations of Stereo principle! While Bach definitely isn’t the founder of double choir, he certainly is one who’s fond of its existence. This motet is not the only example of Bach’s music including double choir, please see St. Matthew Passion if you’re interested!

Don’t you realize what this means? The greatest counterpoint architect in history is fully aware of the left-right split audio and its benefits! Oh god, what would we do if he learnt about binaural, surround or fully spatial audio??

Bach3D: Spatializing the BWV 857 Prelude & Fugue in F minor from WTC vol. 1

I started this project back in september of last year. Raumklang (Spatial Audio) Seminar given by dear Ludger Brümmer and Joachim Goßmann was already one of the shiniest Musikdesign classes I spotted on the semester courses catalogue. History of spatial audio is so much more interesting and fuller than you think; I would say it is the subject of another blog post. Shortly, our project with the Trossinger Laptop Ensemble last year used some elements of Spatial Audio in the amazing studios of ZKM in Karlsruhe, so I already had some knowledge of Quadrophony (surround with four speakers) and how it should sound like. Coincidentally in the same week I had the chance to tour the insides of the main Organ in our University. Being fascinated by both concepts, this idea of merging them came through.

A prelude and a fugue, each with 4 voices. Plan is simple: Record them separately and bring them together in Zirkonium while moving them through the space. I even picked different register combinations for each voice, which is not possible normally. Playing the bass voice was tricky since getting the deep voices I wanted required me to play the pedals, and my feet can’t come close to the dexterity needed for a Bach fugue voice. But hey, since I’m recording each voice separately, I ended up lying face-down on the stool and playing it with my hands! I’ve also managed to do the dynamics on the Organ alone without relying on audio editing, which was a stretch goal I had in mind from the very first moments of brainstorming.

Gabriel asks: Why do the voices move like that?

Whilst I was working on the piece in the Klangpavillon yesterday, my friend Gabriel Engelen accidentally became one of the first people to hear what my project sounds like. First question he asked was related to the complicated movement patterns you can see in the right hand side of the Zirkonium app screenshot above. While the patterns don’t follow a strict ruleset in relation to the music, they’re still closely related to how the individual voices “feel” like they’re moving. Dissonances make the journey to the next destination more squiggly, while consonant harmonies result in tidier curves and straight lines. Aggressive modulation means aggressive movement on the plane for that specific voice, or a standstill translates to one in means of both harmony and planar movement. This answer does a pretty good job at summing up my vision of algorithmic/programmed music: Following what your ear wants instead of defining a blindly (deafly?) decided set of strict rules. Thanks for the feedback Gabriel!

I’m looking forward to the performance later today. 😀

2 comments